Cambodia

Grant distribution

Latest Voices

Open Calls for Proposals

28 Empowerment grants

28 Empowerment grants  6 Influencing grants

6 Influencing grants  18 Innovate and learn grants

18 Innovate and learn grants  2 Sudden opportunity grants

2 Sudden opportunity grants -

No Open Calls at the moment in this country. Come back later!

-

The Kingdom of Cambodia, commonly known as Cambodia, is one of the four Southeast Asian countries where Voice is active. Oxfam is coordinating Voice in the country. We live in a rapidly changing world – some changes may be for the better – others not so much. In order to continue to ground Voice in local lived realities, a country context analysis is organised every other year, engaging many stakeholders, grantees and rightsholders. The analysis is used to frame Calls for Proposals, to support the applications of grant-seekers and to advance the overall learnings. Below follows a summary of the exercise conducted in 2022, capturing the many views and perspectives of Cambodians The summary is structured by presenting the big picture and slowly but surely to zoom in on the voices and aspirations of the rightsholders and to zoom out again by sharing the way forward for Voice. This page can also be downloaded at the bottom of the page. A full report and previous versions can be availed to you upon request.

Zooming out

The big picture

-

The Human Development Index is an index that combines data on life expectancy, education, and per capita income to rank countries. While the overall HDI has been improving slowly over the last few years, Cambodia’s ranking has remained the same between 2016 - 2019.

-

The IHDI measures the human development cost of inequality, or the overall loss to human development due to inequality. The closer to 1 the more equal a society is. The IHDI can inform policies towards inequality reduction. Inequality has been decreasing in Cambodia, albeit slowly. For some rightsholders group, such as the elderly this has not led to improved standards of living (yet).

-

The GII is an inequality index, measuring the human development costs of gender inequality economically, health- and education-wise. The closer to 0, the better. Gender equality has only marginally improved over the last few years in Cambodia.

-

According to the independent Civicus Monitor which started in 2016, civic space continues to be Repressed in Cambodia. This is also because of restrictive NGO laws (LANGO), the State of Emergency Law and the draft Public Order Law. Opportunities for change continue to exist especially at local level as Voice grantees have shown.

Behind the numbers

In more than two decades of rapid expansion of a vibrant and pluralistic civil society, Cambodia painted a worrying picture of its economy, governance, and political progress in this context analysis update conducted for the period 2020-2022. Issues of political and social integration, the stability of democratic institutions, the rule of law, political participation, resource efficiency, and sustainability have all contributed to this perceived situation. Cambodian civic space has shrunk dramatically since 2013. Rights, advocacy groups, critics of the government, and the media have been targeted, resulting in several groups being forced to close and individuals being prosecuted.

Political shifts

Local government elections occurred in June 2022. More than 82,700 candidates from 17 parties contested the elections, which could be viewed as a litmus test for the national government election in 2023. At the same time, Cambodia’s political landscape continues to shift with the space for amplifying the voices of rightsholders getting smaller and smaller. However, there is room for dialogue with the government, particularly on technical issues. Before the pandemic, there were biannual consultation meetings between a prominent group of Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) and government representatives, which provided a platform for dialogue and clarification of misunderstandings. However, since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the meeting has not been held.

In addition to the increasingly hostile environment, many CSOs lack adequate capacity at both organisational and technical levels. This exposes them to the risk of regulatory clampdowns and diminishes their legitimacy and accountability in the eyes of authorities and the public. This also adversely impacts their long-term sustainability.

Economic shifts

Cambodia’s economy is in a stage of critical transformation after sustaining high growth over the last decade. The country is moving toward becoming a low-middle-income country. This will require comprehensive structural reforms to strengthen economic diversification and competitiveness while ensuring sustainable economic growth with equitable redistribution of wealth. Cambodia continues to have a severe infrastructure gap and would benefit from greater connectivity and rural and urban infrastructure investments. Further diversification of the economy will require fostering entrepreneurship, expanding the use of technology, and building new skills to address emerging labour market needs.

Economic and environmental issues affecting Cambodia include rising living costs, post-pandemic economic recovery, and the plight of the Mekong River, where fishing communities have suffered a dramatic drop in fish catches due to climate change, dam construction, illegal fishing, and a three-year drought. Global fuel and agricultural costs and the absence of foreign tourists due to the pandemic are also significant factors affecting the informal economy (about 80% of Cambodia’s GDP). As a result, the Ministry of Finance has allocated about $ 1.2 billion to boost the economy. The government has also established a $200 million reserve fund, its first, to help address the pandemic’s impact on the poor directly.

The changes in global economic and political activity are reducing the influence of ‘traditional world powers,’ and a multipolar, diversified set of regional forces is emerging. While the European Union (EU) partially suspended Cambodia’s trade preferences in August 2020 after finding systematic rights violations, bilateral trade between Cambodia and China increased by 20 percent to US$ 3 billion during the first quarter of 2021.

Social shifts

In the last two decades, significant progress has been made on human development. more children are going to school and average incomes have increased. “Education 2030” is promoted by the government as a new all-encompassing approach to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for children, youth, and adults while fostering lifelong learning opportunities for all. However, employment predominantly remains concentrated in low-skilled occupations, with only 14.3% of the workforce employed as skilled labour. Accountable and responsive public institutions will also be critical. For example, only 6.6% of the elderly population currently receive any form of pension.

(Visible) Power shifts

There has been progress in recognising the support needs of People with Disabilities (PWDs). However, discrimination still exists in the general community’s perception of “disability”, equal access to employment, availability of reasonable accommodation in education and training, physical accessibility to buildings, transport, and services.

Women’s political leadership does seem to be improving evidenced in the increased representation of women at the national, provincial, district, and commune administration levels. The number of female representatives in parliaments has almost doubled. However, there are power limitations for women, especially those who work in decision-making roles in government institutions. As a result, they sometimes cannot express their views in the decision-making process. On the other hand, indigenous women have increasing confidence to voice their needs and issues and are more likely to raise complaints against the company and/or high-ranking officials who take their land.

It is noted that families and pagodas are the main institutions on which the elderly depend (as traditional safety nets), but evolving social changes are creating a new trend requiring the elderly to live by themselves. Even though they have more space and opportunities to express their views and demands and feel more confident in raising their voices through their representatives, including the Cambodia Aging Network (CAN), they still face age discrimination from potential employers, sometimes their children, and are often excluded from family decision-making.

Young people present a potential for change and are known to adapt quickly to changing circumstances. Indigenous youth are more confident in revealing their identity as Indigenous People (IP) on social media, while previously, they felt ashamed to expose their identity to the public. Youth who work as NGOs volunteers have opportunities to participate in the decision-making process and commune meetings to share their concerns and information. Commune council members are open and accept their inputs.

While supportive statements by government officials seeking to uphold non-discrimination on the basis of Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression (SOGIE) grounds are welcomed, it is imperative that these words and commitments are transposed into concrete legislative and policy measures. It is also important to create proactive government-led campaigns to champion the non-discrimination of LGBTI people. Some progress in promoting the interests of LGBTI people has been made through social media and the community at large. LGBTI people are now more confident and encouraged to participate and be represented in community activities and events. They are also using their talents to gain employment.

COVID-19 related shifts

The COVID‐19 pandemic hit Cambodia’s main drivers of economic growth and paid employment —tourism, manufacturing exports, and construction. People working in the marginalised informal sectors have faced major challenges, especially regarding working conditions, security of livelihood, violence, exploitation, discrimination, and social exclusion. Job losses and reduced income have forced many marginalised workers to struggle for basic necessities. Many suffered from increased stress and anxiety due to loss of income, social distancing, and movement restrictions.

The pandemic affected the lives and livelihoods of garment sector workers in particular, exacerbating inequalities and deepening poverty. Many workers took loans as a coping strategy because many workers, particularly those in the informal sector, lacked access to adequate social safety nets. The government provided garment workers who were suspended due to the pandemic with US$40 per month in cash assistance. It also approved a one‐time post lockdown emergency cash assistance pay-out in June 2021 that benefited garment workers. The emergency cash transfer was also applied to other marginalised people during the COVID-19 crisis, particularly PWDs, the elderly, and poor families. On the other hand, the poorest people in indigenous communities do not have ID cards or legal documents that might enable them to access social protection schemes.

Inequalities in many areas, such as employment and payment, division of domestic labour, decision‐making, and participation faced by women and girls were further exacerbated during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Domestic violence against women increased during the crisis and the pandemic also threatened many persons with disabilities as they faced inequalities that left them more exposed, and this was heightened for women and girls with disabilities.

The pandemic has been a catalyst to rethink how agencies can work more creatively and effectively. Online platforms were used during COVID-19 for meetings, and people used social media to express their views on things other than sensitive issues and political agendas.

Zooming in

Voices behind the picture

Even though many elderly people have more space and opportunities to express their views and feel more confident in raising their voices through their representatives, they still face age discrimination. Forms of discrimination may range from exclusion from job opportunities to exclusion from family decision-making. During the COVID-19 pandemic, cash transfers for the elderly were distributed as per the sub-decree on Allowance for People with Disabilities (PWDs), but it seems likely that the government will reduce its funding gradually over time. Older People Associations (OPA) are unable to meet requirements of the government’s Law on Associations and NGOs (LANGO) because they are community-based associations working without financial support.

Many young people face age discrimination and financial constraints, have limited freedom to express their views, lack soft skills and experiences, and are prone to migration for work. Young Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) people still face discrimination from their families and communities, and LGBTI youth who “come out” on social media are often criticised. Child marriage of indigenous teenage girls is one of the major issues in Indigenous People (IP) communities leading to reproductive health problems. This is within the context of wider lack of access to health services. Young environmental rights defenders also face barriers and pressure from local authorities in doing their work. COVID-19 impacted the lives of the youth, including education, finance, and creating the threat of online sexual abuse. Illegal drug use by youth is also an emerging trend. Greater digitalisation presents an opportunity to promote inclusivity but creates risks that also need to be addressed.

The current situation for People with Disabilities (PWDs) in Cambodia seems to be improving. Yet, discrimination still exists in the community’s perception of “disability”. Progressively, during COVID-19, PWDs were supported by the government through a shock-responsive social protection scheme in the form of a monthly cash transfer. A poverty policy framework was piloted in 17 provinces. However, the employment rate of PWDs remains very low due to non-compliance with the law related to the employment of PWDs and lack of penalties for non-compliance. At the same time, PWDs are reluctant to claim equal benefits.

Indigenous People (IP) communities live mainly in the forested plateaus and highlands of north-eastern Cambodia. Land registration rates remain low, with only some small plots of community land registered and recognised by the government. Natural forests, the main sources of IP economy and representation of their culture and identity, face continuing destruction, and conflict with private companies over their community land remains unsolved. IP communities are vulnerable to sexual abuse committed by rubber plantation workers. Rape cases of women and girls are increasing. In addition, IP students have dropped out of school during the COVID-19 lockdown, leading to increased child marriages.

Commune members still have a limited understanding about the needs of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) community. While employment opportunities are starting to be created, legalisation still has not happened. As a result, LGBTI community members are yet to be legally protected against discrimination, bullying, and violence. The inability to marry under the law excludes LGBTI people from the rights others enjoy and perpetuates increasing vulnerability, well-being, and harmony.

Cambodia still rates poorly on gender equity, although women’s political leadership has improved. COVID-19 significantly affected the economic status of vulnerable women, especially those who work in the private and informal sector, because of the lockdown and restrictions on group gatherings. Vulnerable women had no income and faced a debt repayment crisis. Domestic violence against women increased during the COVID-19 crisis. An entrenched patriarchal mindset causes barriers to women seeking to develop and implement policies. Women facing multiple and intersectional forms of discrimination such as women living with HIV, women with disabilities and indigenous women struggle with internalised stigma and negative mindsets about themselves. They often lack knowledge, information, and opportunities to participate in decision-making.

Their aspirations

Cambodia is gradually moving forward with critical policies, guidelines, and commitments to be more supportive of various rightsholder groups. However, more needs to be done. Some aspirations and change agendas for each rightsholder group are highlighted below:

Elderly people:

- For the National Aging Policy (2021–2025) to be more feasible and adaptable, and for the government’s “family package” to be pursued.

- For policymakers and development partners to pay more attention to policies and implementation of legislation. Structures like the commune council should be vehicles to raise the voices of the elderly.

- For psychological and mental health services to be available for the elderly.

- For international initiatives, such as the Madrid International Agreement, to be considered by Voice countries.

- For young people to be encouraged to think “long term” and prepare better for their retirement.

Youth:

- For collective encouragement of voices of LGBTI, PWDs, and IP youth through interagency partnerships (among NGO Government and private sector players) and support for bringing their voices to advocacy to regional or global levels.

- For IP youth to be provided with vocational training, especially in farming, and with educational scholarships. The small grant project, such as NOW-Us Award to be continued for IP youth communities.

- For young people to be encouraged to think “long term” and prepare better for their retirement.

- For increased awareness concerning the needs of the LGBTI community to reduce bullying and discrimination faced by this group. This includes education on sexual health and mental health.

- For youth from IP communities to be equipped with entrepreneurship concepts and skills.

People with Disabilities (PWDs):

- For promotion of economic empowerment of PWDs.

- For alignment of the Voice program with the ASEAN strategic goals for PWDs.

- For disability inclusion to be promoted in all sectors (health, education, urban and planning, transportation).

- For young PWDs to be engaged in income generation activities and not be dependent on their families.

- For all public and private providers to enforce awareness of laws/regulations and guidelines for disability inclusion.

- For youth with disabilities to be equipped to take the lead in influencing work and mainstreaming disability rights.

- For Voice to ensure disability-inclusive environments, and work on intersectionality.

LGBTI people:

- For LGBTI people to be empowered to come out safely.

- For awareness-raising at the community level and vocational training like short courses to be organised for income generation and independence.

- For social enterprises to be established and support to be offered for national advocacy for legalisation of same-sex marriage.

- For enactment of an anti-discrimination law and law for gender recognition regarding SOGIE.

- For amendments to be made to the Constitution to allow same-sex legal marriage.

- For adoption of comprehensive legislation and policy that explicitly prohibits LGBTI discrimination.

- For effective measures to be enacted to combat and punish discrimination and violence.

Indigenous People (IP):

- For there to be continued empowerment of indigenous communities to be able to voice their concerns to local authorities and the development of a master plan and long-term vision for the future of all IP communities.

- For strengthening the solidarity of IP community and for IP youth to prepare themselves to adapt to the changing context outside their community, including digital.

- For research studies to be conducted on IPs and IP cross-community networks to build knowledge and skills, mainly in digital technology for women and girls. For more collaborative work among relevant ministries, NGOs, and women’s networks, and rightsholder groups to encourage their participation in designing projects.

Women facing exploitation, abuse and violence (WEAV):

- For local authorities implementing policies or guidelines to have more knowledge on gender justice and be open to accepting the “new gender norm” that promotes gender equality for all.

- For development partners and donors to continue following their priorities to support small and local organisations to promote the education of children of most marginalised groups.

- For CSOs to collect evident-based information to advocate with the government for policy change, enhance their advocacy approaches and make the best use of social media, digital platforms, and technical expertise.

- For policymakers to make policy changes, engage sub-national levels in enforcing related policies and laws, and address the harmful use of social media.

- For opportunities to be created for Women Living with HIV (WLHIV) to participate in the movement and express their views and improve their livelihoods.

- For greater awareness of existing laws/policies and promotion of policy/law enforcement.

Zooming out

Fostering change

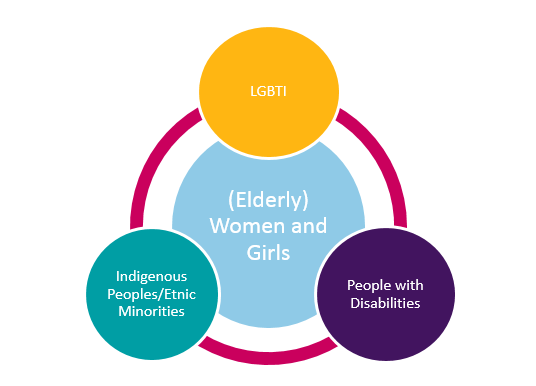

Voice is unique in addressing issues through an intersectional approach that creates spaces for all rightsholder groups to voice their concerns. The programme should further look for new initiatives to address the issues and needs of support of rightsholder group and to scale up based on lessons learned and good practices.

In terms of fostering change, the analysis makes the following recommendations for further supporting rightsholders:

- The current focus on rightsholder groups must be retained. The express separation of youth initiatives from the elderly rightsholder group should be made further clear.

- Continue reaching out to rightsholder groups and organisations that are hard to reach or the “invisible group” including people with mental health conditions, people with hearing or vision impairments, and people who use drugs, particularly those in the indigenous community and among women.

- Consider increasing support on mental health issues since it is an emerging need affecting all rightsholder groups particularly post the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Give more focus on the theme “promote access to resources and employment” by promoting the economic empowerment of all rightsholder groups who were badly impacted during the pandemic. Strategies like youth innovation, business incubation, entrepreneurship, and advice to assist youth and women across all the rightsholder groups in expanding the entrepreneurship concept and skills.

- Online platforms were used during COVID-19 for meetings, and people used social media to express their views on things other than sensitive issues and political agendas. The adoption of the National Internet Gateway law is tightening access to freedom of expression on social media and online platforms which could become another emerging risk to be considered.

- Voice should continue to build a communication strategy that incorporates the principles of “hope-based communication” to support the rightsholder groups through visual and auditory media designed to encourage advocacy, dialogue, the sharing of ideas, and collaborative action.

- The Voice Linking and Learning Platform will play a crucial role to generate knowledge exchange, resource mobilisation and amplification of stories of the rightsholder groups.

-

-

Grants

-

Grantee

![Louder Voices for Social Protection through I-SAF or I-SAF for Social Protection]()

Louder Voices for Social Protection through I-SAF or I-SAF for Social Protection

Advocacy and Policy Institute (API) -

Grantee

![Protect and improve our Kui lan]()

Protect and improve our Kui lan

Organization for the Promote of Kui Non-Governmental Organization - Call for Proposal

“Nothing about us Without Us”: V- 22207 -KH-IL NOW-Us! Awards Cambodia, Round II

closing date: 24 Jun 2022Closed -

Grantee

![Passing the torch: Land Rights Now for Indigenous Youth]()

Passing the torch: Land Rights Now for Indigenous Youth

International Indigenous Peoples Movement for Self Determination and Liberation (IPMSDL) - Call for Proposal

Safeguarding Our Digital Rights and Digital Citizenship: V -22200- KH-SO

closing date: 31 Jul 2022Closed -

Grantee

![Our Turn! Voicing out multiple marginalisation through intersectional solidarity]()

-

Grantee

![Promote disability-inclusive in social protection]()

Promote disability-inclusive in social protection

Representative Self-Help Disabilities Organization Batheay (RSDOB) -

Grantee

![Empower Persons with Disabilities in Informal Economy]()

Empower Persons with Disabilities in Informal Economy

Independent Democracy of Informal Economy Association -

Grantee

![FACT: Feminist Approaches to Counter-Trafficking]()

FACT: Feminist Approaches to Counter-Trafficking

International Womens Rights Action Watch Asia Pacific (IWRAW Asia Pacific) -

Grantee

![Improving Working Conditions & Rights of Cambodian Domestic Workers]()

Improving Working Conditions & Rights of Cambodian Domestic Workers

Independent Democracy of Informal Economy Association -

Grantee

![DEAFLoud]()

DEAFLoud

Lao Disabled Women’s Development Centre host for Psycho-Education & Applied Research Center for the Deaf (PARD Vietnam) -

Grantee

![Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures]()

Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures

International Women's RIghts Action Watch Asia-Pacific -

Grantee

![Inspire]()

Inspire

BABSEACLE Foundation host for International Drug Policy Consortium and Indonesian Act for Justice - Call for Proposal

Empowerment Accelerated!: Cambodia Empowerment Grant V-21175-KH-EM

closing date: 07 May 2021Closed - Call for Proposal

Shine through! Claiming Cambodian Women's Voices (Post) Pandemic: Cambodia Influencing Grant V-21174-KH-IF

closing date: 07 May 2021Closed - Call for Proposal

Voice(s) Connected & Amplified in Cambodia: Linking & Learning Facilitation V-21167-KH-IL

closing date: 26 Feb 2021Closed - Call for Proposal

Celebrating Inclusion: Cambodia Innovate and Learn Grant V-20158-KH-IL

closing date: 25 Jan 2021Closed

Grantee![Louder Voices for Social Protection through I-SAF or I-SAF for Social Protection]()

Louder Voices for Social Protection through I-SAF or I-SAF for Social Protection

Advocacy and Policy Institute (API)Grantee![Protect and improve our Kui lan]()

Protect and improve our Kui lan

Organization for the Promote of Kui Non-Governmental OrganizationCall for Proposal“Nothing about us Without Us”: V- 22207 -KH-IL NOW-Us! Awards Cambodia, Round II

closing date: 24 Jun 2022ClosedGrantee![Passing the torch: Land Rights Now for Indigenous Youth]()

Passing the torch: Land Rights Now for Indigenous Youth

International Indigenous Peoples Movement for Self Determination and Liberation (IPMSDL)Call for ProposalSafeguarding Our Digital Rights and Digital Citizenship: V -22200- KH-SO

closing date: 31 Jul 2022ClosedGrantee![Our Turn! Voicing out multiple marginalisation through intersectional solidarity]() Grantee

Grantee![Promote disability-inclusive in social protection]()

Promote disability-inclusive in social protection

Representative Self-Help Disabilities Organization Batheay (RSDOB)Grantee![Empower Persons with Disabilities in Informal Economy]()

Empower Persons with Disabilities in Informal Economy

Independent Democracy of Informal Economy AssociationGrantee![FACT: Feminist Approaches to Counter-Trafficking]()

FACT: Feminist Approaches to Counter-Trafficking

International Womens Rights Action Watch Asia Pacific (IWRAW Asia Pacific)Grantee![Improving Working Conditions & Rights of Cambodian Domestic Workers]()

Improving Working Conditions & Rights of Cambodian Domestic Workers

Independent Democracy of Informal Economy AssociationGrantee![DEAFLoud]()

DEAFLoud

Lao Disabled Women’s Development Centre host for Psycho-Education & Applied Research Center for the Deaf (PARD Vietnam)Grantee![Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures]()

Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures

International Women's RIghts Action Watch Asia-PacificGrantee![Inspire]()

Inspire

BABSEACLE Foundation host for International Drug Policy Consortium and Indonesian Act for JusticeCall for ProposalEmpowerment Accelerated!: Cambodia Empowerment Grant V-21175-KH-EM

closing date: 07 May 2021ClosedCall for ProposalShine through! Claiming Cambodian Women's Voices (Post) Pandemic: Cambodia Influencing Grant V-21174-KH-IF

closing date: 07 May 2021ClosedCall for ProposalVoice(s) Connected & Amplified in Cambodia: Linking & Learning Facilitation V-21167-KH-IL

closing date: 26 Feb 2021ClosedCall for ProposalCelebrating Inclusion: Cambodia Innovate and Learn Grant V-20158-KH-IL

closing date: 25 Jan 2021Closed -

Link + Learn

Voice in Cambodia

The Point, 3rd Floor, U08-09, No 113C, Mao Tse Tung Blvd.,

Tuol Svay Prey I, Beung Keng Kang, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Tel: +855 23 885 412, +855 23885413